News that a mysterious illness was sending people to the hospital in Wuhan, China, first surfaced in late December of 2019. On Jan. 11 of 2020, the disease was tied to what scientists were calling a “new coronavirus.” The virus quickly spread to other nations in Asia, and by Jan. 24, it was in Europe as well. The U.S. saw its first confirmed cases in late January when five people who had traveled to Wuhan fell ill with the disease.

By February, a major outbreak had occurred aboard a cruise ship, Italy was being devastated, and the CDC warned Americans to begin preparing for the spread of the virus in the U.S. Those fears materialized in early March with a significant outbreak in Washington State. New York City would bear the brunt next. The rest of the nation was not far behind.

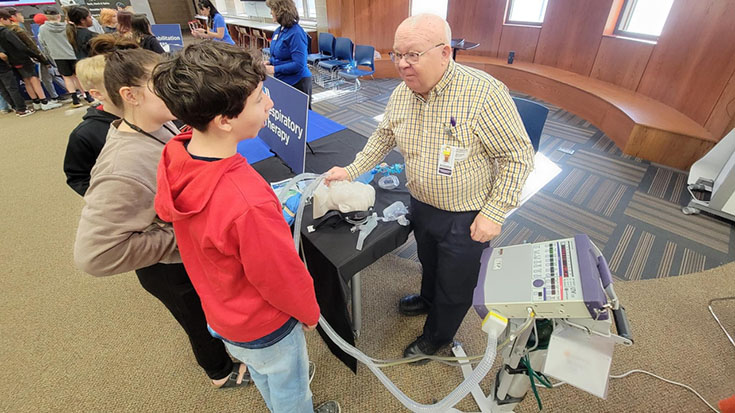

It was a worst case scenario for everyone in health care, and respiratory therapists were in the middle of the fray from day one. We asked AARC members to share their thoughts on 2020 and the lessons they learned during the pandemic.

Pivoting to a new reality

Kenny Miller, MEd, MSRT, RRT, RRT-ACCS, RRT-NPS, AE-C, FAARC, educational coordinator and wellness champion for respiratory care services for the Lehigh Valley Health Network in Allentown, PA, says his hospital began addressing the pandemic daily beginning in early March.

“At 0700 there was a daily multidisciplinary team phone call that discussed and assessed current clinical practice germane to the COVID patient population,” he said. “This team included respiratory care leadership, the departmental medical director, infection control, hospital administration, and the ICU directors.”

The group tackled topics ranging from infection control to equipment levels to practice changes, and all the information was placed in a staff folder that could be reviewed and revised as needed. The hospital continued with the daily meetings until early July.

At Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, MI, Department Director Alicia Wafer, MBA, RRT, and Manager Jonathan Vono, RRT, say the pandemic catapulted their department from a typical ventilator load of 75-85 per day to more than 100 within a week’s time.

“COVID-19 changed our behavior and physical plant so very radically overnight,” Vono said. “Non–emergent surgeries stopped, the ER was overflowing, and hospital beds were filling with patients coming in with suspected COVID, or presenting with COVID symptoms, while we still had patients coming in sick and injured.”

As clinicians provided bedside care, department leaders worked closely with physician medical directors and other providers across all disciplines to create and revise system policies to meet the demands being placed on operations due to COVID-19. Their primary focus was on making the changes that made the most sense from a patient and staff safety standpoint. “Changes were communicated to teams in huddles, via electronic huddle boards, and via email,” says Wafer.

Dealing with interruptions

For Caitlin Coppock, RRT, RRT-ACCS, and her colleagues at INTEGRIS Canadian Valley Hospital in Edmond, OK, the early days of the pandemic were felt in terms of interruptions in their supply chains. “We were not of priority to get some of the disposables we use, so we had to become very efficient in using them, knowing we needed to try other modalities if patients could tolerate them, to avoid depleting certain equipment supplies we had,” she said.

They learned some early lessons from their initial encounter with a confirmed case, which came in mid-March, as well.

“Our first positive system-wide knocked out an entire ICU of nurses and RTs and a few physicians because of exposure at the time,” she said. The patient was not on the radar for COVID, but ultimately tested positive. The experience led to an immediate increase in measures to protect staff and other patients from aerosol generating procedures.

Lisa Ball, MHA, RRT, RRT-NPS, RRT-ACCS, RPFT, COPD-ed, CTTS, NCTTP, works in the IBMC pulmonary lab at INTEGRIS Health in Oklahoma City and she says the pandemic shut down many of their services at first.

“We initially canceled all PFTs, bronchoscopies, and 6MWTs for about two weeks while we determined if or how we could safely perform these services,” she said. Of the five full time RTs in the lab, two decided to furlough, one volunteered to work on the COVID unit, and the other two remained in the lab.

“For about four weeks, before COVID testing was available, we only performed emergent bronchoscopies and PFTs,” Ball said. “Our emergent PFTs were for patients suspected of amiodarone toxicity, pre–chemo clearance, and post–lung transplant suspected of rejection, liver transplant workup, and LVAD/heart transplant work up.” Lung transplants were canceled because neither donors nor recipients could be tested.

The lab was able to fully open after about six weeks. Thankfully, their PFT rooms are all negative airflow, and they removed everything in them that was not necessary for testing. RTs wear N-95s, a face shield, and gloves, and patients are prescreened with a temperature check and symptom survey when they enter the hospital. All bronchoscopy patients must have a negative COVID test within seven days of their procedure.

Ensuring safe travels

The flight team at AdventHealth in Orlando, FL, transported their first patient under investigation (PUI) for COVID-19 on Mar. 23. Until then, they focused solely on safety.

“We had an unofficial stand-down to make sure we were all on the same page,” said Fight Therapist Jon Inkrott, RRT, RRT-ACCS. “We had to make sure we had buy–in from our dispatchers and our mechanics and our pilots and ultimately, the entire crew.”

That first patient turned out to be negative, but the experience gave the team confidence that they had put all the necessary safety precautions into place. Since then, they’ve transported 20 PUI/positive cases in the aircraft and nearly 1,800 by ground. Among the latter group, 39% have ultimately tested positive for the virus.

Inkrott says the challenges they faced in the transport environment transcended those faced in the typical hospital setting. For one thing, it is not possible to communicate in the aircraft while wearing a North mask or an N-95 due to the helmet microphone.

“So, we purchased masks with an integrated microphone in the mask, which made communication much easier and normal,” he said. They also had to create a proning protocol to safely transport patients in the ambulance.

Changes in practice

While mechanical ventilation was the mainstay of treatment for people with severe COVID-19 during the early days of the pandemic, the high mortality rate for patients receiving invasive ventilation soon drove RTs and their colleagues in medicine and nursing to consider alternatives.

“In the early phase, the threshold for intubation and ECMO was very low,” said Kenneth Miller. “After several months, those thresholds were elevated. Every intervention was utilized to prevent intubation and ECMO.”

At Henry Ford in Detroit, therapists began using HHFNC, NPPV, and proning relatively quickly, says Rena Laliberte, BS, RRT, clinical specialist in education and the emergency department.

“Our system kept up with daily CDC recommendations and shared and learned information as updates occurred, and our practice changed based on those updates,” she said.

Over the coming months, they would treat more than 3,000 patients with COVID, and among that group about 900 were ventilated. Laliberte worked in the ED during the entire surge, and says she feels proud of the work she did there.

“I knew I was doing exactly what was recommended to help treat and save the patient,” Laliberte said. “When they improved, it was a very rewarding feeling.”

Caitlin Coppock says the initial policy to intubate early if the patient’s work of breathing and O2 demands required more than a flush oxymask soon gave way to a less invasive paradigm at her hospital in Oklahoma.

“Over the weeks and months to follow we were slowing down pushing mechanical ventilation and instead trying proning while on HFNC,” she said.

They saw some success, but she emphasizes that for some patients, those tactics just prolonged the inevitable need for invasive ventilation.

“Patients that are very critically ill still do not have great long–term outcomes,” she said.

Troy Whitacre, RRT, RRT-ACCS, clinical coordinator in the medical ICU at MU Health Care in Columbia, MO, says they were intubating their patients when Fio2 was greater than .60 on the HHFNC when the pandemic began.

“Now, if the patient is mostly asymptomatic with adequate mentation, we may not intubate patients on 1.0 fio2/60lpm HHFNC until there is a clear indication — such as increasing fatigue, confusion, or frequent drops in Spo2 to less than 88,” he said.

Beyond adult acute care

The pandemic has drawn great attention to the work RTs do in adult acute care, but its effects have been felt by therapists working in other settings too. Gary Wong, MBA, RRT, and Rick Morgan, BPA, RRT, RRT-NPS, represent two ends of the spectrum.

Wong is director of respiratory services at Islands Skilled Nursing and Rehabilitation, a 42-bed post-acute and respiratory care community specializing in short–term rehabilitation, ventilator, and tracheostomy care in Honolulu, HI. As hospitals on the island of Oahu began to fill up, they needed to discharge some of their patients to his facility to free up critical care beds, and that meant he and his colleagues had to make some immediate changes.

“Without all the physical plant advantages of piped in oxygen and suction, private rooms, and negative pressure rooms, we had to adapt and standardize our ventilator to the VOCSN, which provided us with the built-in oxygen and suction capabilities,” Wong said. “We followed the recommended CDC guidelines to control aerosol generation with HEPA filters, inline suction catheters, and inline Aerogen nebulizers.”

They stockpiled inhalation water for their heaters, ventilator circuits, and HEPA filters as well, in anticipation of supply chain and inventory disruptions that were being predicted due to the surge in demand created by the pandemic.

Morgan and his colleagues at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg, FL, may not have had many COVID patients — indeed, the only good thing about the pandemic is that it has largely spared children — but they have had their share of inventory disruptions as well.

“We have had to be innovative in our problem–solving solutions when our everyday supplies have become not available to us because they were consumed by the adult populations, including ventilators and components needed to carry out respiratory therapy across the board,” Morgan said.

The pandemic has fostered a greater deployment of technology used to connect remotely in his facility as well, and that has increased productivity, since people can now connect to a meeting from any location.

Morgan believes the pandemic has highlighted the importance of resiliency and collaboration among everyone in health care. Only by working together and being willing to give and take can patient needs still be met.

A learning experience

At this point, therapists across the country have endured months and months of a pandemic that is still gripping the nation, despite the rollout of promising vaccines. What have they learned the process, not just about best practices in treatment, but about themselves and their colleagues in the hospital?

The RTs we talked to for this article have this to say —

What I have learned is how versatile I am when I need to be, and that I can safely care for my patients while protecting myself from this virus. The only practice we have changed is that we wear a mask and face shield and we keep all of our supplies in the cupboards instead of on the counters. We will continue this practice. We thought we were practicing good disinfection techniques prior to the pandemic, but found that we could do better. — Lisa Ball

Lesson One — take your time, be deliberate in practice, and very methodical in protecting yourself with proper PPE and those around you. Lesson Two — be patient, take a breath and keep moving forward. It was a very stressful time and there was little time for breaks and breaths. It would have been easy to snap and break down. But you cannot. You have to keep your focus, remind yourself who you are, what you do, and what you mean to that patient. They are counting on us and we have to rest when we can and then remember who we are! — Rena Laliberte

A pandemic exposes health care professionals to a great deal of personal anguish—especially true when resources are limited and care is the best you can deliver, but not what you are usually able to give. More resources need to be focused on frontline staff to make sure their emotional needs are being met. Hospitals and departments need to reassess supply reserves, including PPE, ventilators, and ventilator accessories, filters, commercial endotracheal securing devices, and such. — Troy Whitacre

First we absolutely have to be diligent in protecting ourselves and holding those around us that we work with to a high standard to protect themselves in every situation. A simple exposure could wipe out the ability to do our jobs and care for those in need. Second, not that this is a new concept, but this has just solidified the need for interdisciplinary collaboration and teamwork; without the participation of all groups of caregivers, we could not help these patients. They require an immense amount of time, knowledge, and care. Lastly, though we have learned a lot and seen some of our best practices implemented and improved outcomes, there seems to still be a long way to go. The percentage of ICU level patients that survive this is still very, very poor. — Caitlin Coppock

I don’t want to say we changed much from a practice standpoint because we’ve been proning patients for years, we’ve been using inhaled pulmonary vasodilators for years, we’ve been careful around highly infectious pathogens for years. What I do believe happened is that we, as a profession, were highlighted and recognized after many years of being under recognized. I am proud to be part of this professional family, from the ICU to the air to the LTACs to the classroom. I am proud to be a respiratory therapist. The lesson we all need to learn is to please self-care. Take a moment to decompress. Reach out to others and debrief, share stories or experiences, cry if you need to cry. Ultimately, just look out for one another. — Jon Inkrott

In the post-acute care environment, it is especially important to keep our patients safe by preventing asymptomatic transmission, wearing our PPE appropriately, and limiting our community contact outside of work. Be vigilant in performing your respiratory assessments and notice any changes in the patient’s condition. In this COVID-19 pandemic the hospitals are discharging more acute skilled nursing patients who may have underlying respiratory and/or cardiac comorbidities that will manifest themselves in oxygen desaturations or respiratory or cardiac arrest. Having the ability to have continuous oximetry monitoring is beneficial. — Gary Wong

The human spirit has been tested by today’s challenges, and it has been inspiring to see these caregivers who have gone above the call of duty, as well as those community members who rallied to take care of caregivers and cheer them on during this pandemic. — Rick Morgan

Email newsroom@aarc.org with questions or comments, we’d love to hear from you.