The ever-evolving role of the RT

To be an RT, one must be highly adaptable and possess the ability to respond quickly to various unpredictable situations. Like many outpatient RTs, I thought my adaptability would be tested when I returned to the bedside in April 2020, ready to manage airways and ventilators. Little did I know that for a respiratory therapist who works in pulmonary rehab, our ability to adapt would soon be tested in new ways. As our Pulmonary Rehab program transitioned to a virtual Pulmonary Rehab, we attempted to predict how a post-COVID-19 patient would present and how we would treat. We looked at multiple lung injury models and kept up to date on the latest resources from organizations such as; the American Thoracic Society (ATS), American Association of Cardiac and Pulmonary Rehab (AARC), the World Health Organization (WHO), the European Respiratory Society (ERS), and the American Association of Respiratory Care (AARC). Based on what we saw in the past, we anticipated they would have some form of interstitial lung disease related to Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS). While this prediction was correct in many cases, a new type of patient with unexpected conditions also emerged that would stretch us to think outside the box regarding treatment and support. As the complexity of the Long-COVID population continues to emerge, this article is an attempt to share what our team has experienced up to this point. Taking into consideration that it is mostly based on expert option with limited research thus far.

Background

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was first detected in December 2019. According to the online Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Tracker, as of August 2021, over 216 million people have been infected worldwide 1. As attempts are being made to stop the spread of the coronavirus, there are also heightened concerns on how to treat those who continue to have post-COVID conditions persisting anywhere from months or longer after the initial infection recovery. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), post-COVID conditions can occur in patients who have had varying degrees of illness during acute infection, including those who had mild or asymptomatic infections. Post-COVID conditions is an umbrella term used by the CDC to refer to a wide range of conditions. The terminology varies and may also be referred to as long-COVID, post-acute COVID-19, long-term effects of COVID, post-acute COVID syndrome, chronic COVID, long-haul COVID, late sequelae, and post-acute sequelae of SARS-COV-2 infection (PASC).2

Long-COVID Presentations

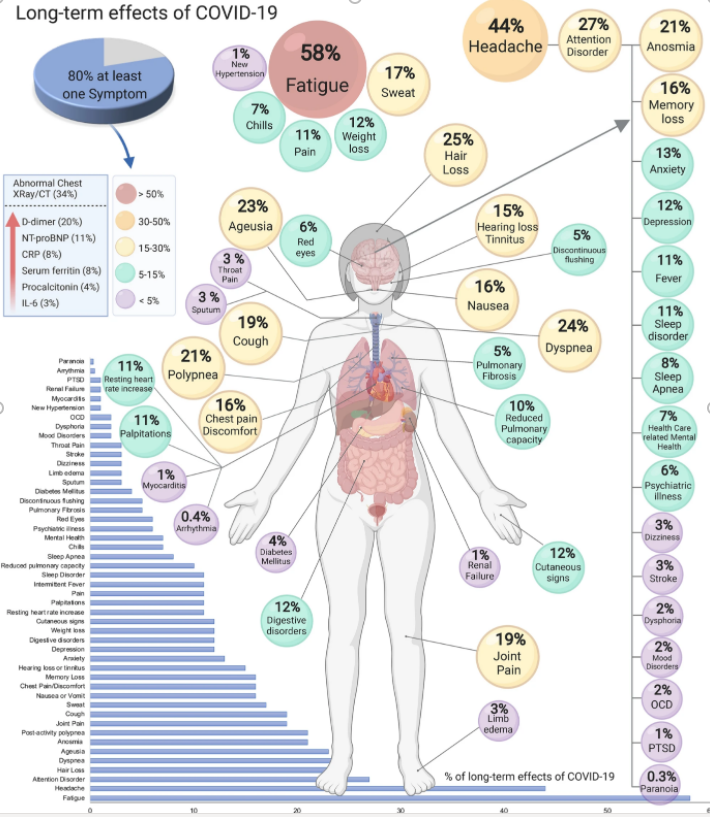

The Oxford Dictionary defines the term sequelae as a condition that is the consequence of a previous disease or injury. The sequelae of COVID-19 can lead to conditions that influence many systems in the body, thus making symptom management quite complex. The figure below is from a meta-analysis published by Scientific Reports, More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The meta-analysis estimated that 80% of the infected patients with SARS-CoV-2 developed one or more long-term symptoms, with the five most common symptoms being fatigue (58%), headache (44%), attention disorder (27%), hair loss (25%), and dyspnea (24%).3

Figure 1

Source: Scientific Reports, More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis

The SARS-CoV-2 virus has the potential to impact nearly every organ system in the body. As scientific evidence evolves on the subacute and long-term effects of COVID-19, experts are working to define the epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management considerations for individual organ system impairment.4

Post-Viral Conditions

Conditions and symptoms associated with post-viral infections is not new. Every day we learn more and more on how to treat and support patients with long-COVID. Recently, experts have begun to compare and contrast other diseases and conditions with mirroring symptoms of long-COVID. Experts have correlated dysautonomia and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) as conditions that could help determine treatment strategies. Dysautonomia refers to conditions related to a disruption in the autonomic nervous system (ANS). The ANS is the part of the nervous system responsible for the involuntary bodily functions such as; breathing, heart rate, blood pressure, digestion, temperature regulation, and hormone function, to name a few. Dysautonomia can cause orthostatic intolerance syndromes, including orthostatic hypotension (OH), vasovagal syncope (VVS), and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS).5,6 Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) is defined by the CDC: “As a disabling and complex illness. People with ME/CFS are often not able to do their usual activities. At times, ME/CFS may confine them to bed. People with ME/CFS have overwhelming fatigue that is not improved by rest. ME/CFS may get worse after any activity, whether it’s physical or mental.” ME/CFS can cause a symptom known as post-exertional malaise (PEM), which can present with high fatigue levels and characteristics similar to depression. Other symptoms can include problems with sleep, thinking and concentrating, pain, and dizziness.7

It’s important to note that not all people with Long-COVID have dysautonomia and ME/CFS. However, it is essential to understand treatment considerations when working with those previously diagnosed or presenting with symptoms related to dysautonomia and ME/CFS, particularly as it relates to PEM and POTS. Exercise may trigger stress responses in their bodies which can cause significant setbacks of long-lasting fatigue and orthostatic tachycardia. Rehabilitation of these patients must be looked at from a multidisciplinary viewpoint. Because dyspnea is a common symptom in these patients, Pulmonary Rehab programs may serve as the intersection to help guide patients to find the appropriate discipline to start their treatment. Some may be better suited for a one on one physical therapy approach with close monitoring, and perhaps progress to the typical Pulmonary Rehab group setting. Others may find the group classes more beneficial because of the emphasis on the breathing component combined with the group support. In either setting, when treating patients with dysautonomia and/or POTS, protocols such as the modified Levine Protocol provide a step-by-step guide for exercising with POTS syndrome. This can support slow safe progression when tachycardia and orthostatic conditions exist.8 An additional exercise resource when working with patients with POTs, is from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, since most of the research comes from the management of POTS in the pediatric population.9When supporting patients with symptoms of CFS, use of a symptom tracker or narrative can support the treatment by having the patient characterize their top three symptoms to monitor. This can help the patient and clinician know how to modulate exertion, and when to incorporate relaxation techniques as not to trigger PEM.10

Pulmonary Manifestations of Long-COVID

There is still much to learn regarding long-term pulmonary conditions and the persistent dyspnea experienced by people after their initial COVID symptoms began. The primary concerns being the long-term impact on lung health and overall functional capacity. It was reported that 30-60% of individuals who recovered from the initial COVID infection continued to present with symptoms such as fatigue and dyspnea.11 Emerging pulmonary function data published thus far shows that lung function appears to be generally well preserved. The prominent spirometry abnormalities are at a reduced diffusing capacity (DLCO) and reductions in total lung capacity (TLC). Functional capacity and deconditioning are present as measured through six-minute walk tests (6MWT) and cardiopulmonary exercise test outcomes.11 In a study performed at the University of Vermont Lung Center, researchers are following patients with persistent pulmonary symptoms post-COVID-19. In a personal communication with pulmonologist Dr. David Kaminsky, he shares: “Our own research so far is showing that those who were hospitalized for COVID still have normal lung function out to a year later, but it is statistically lower in lung volumes, DLCO, and 6 min walk distance compared to those who did not require hospitalization.” As data continues emerging, so do the questions on how to treat these symptoms and support patient rehabilitation so they can return to their pre-COVID lives.

Pulmonary Rehabilitation and dyspnea with Long-COVID

At the University of Vermont Medical Center (UVMMC), the Pulmonary Rehab program started to see referrals for “persistent dyspnea related to post-COVID syndrome” sometime around September 2020. In addition to dyspnea, patients presented with chest pain, loss of ability to speak, loss of smell, tachycardia at rest, diaphoresis at rest, extreme fatigue, brain fog, and joint pain, and migraines, to name a few. But, as if all the above weren’t already perplexing enough, one of the most baffling symptoms was extremely high dyspnea ratings when spirometry and imaging were primarily normal.

Respiratory Therapists who work in Pulmonary Rehab are adept at supporting people with disorders of breathing and who are extremely limited physically due to their dyspnea. Education in breathing retraining techniques such as pursed-lip breathing (PLB) and diaphragmatic breathing can be the “miracle breath” to assist patients with returning them to their previous lives and activities. Exercise progression is typically slow, and the management of dyspnea is the priority so as not to trigger a fear related to exercise. For many, this is the go-to treatment for helping to support the symptom of persistent dyspnea and deconditioning related to long-COVID. However, this approach was less beneficial in some cases, as the patients found the breathing techniques challenging and exercise was limited. These patients showed more complex respiratory symptoms such as tachypnea with resting respiratory rates greater than forty, primary mouth breath breathing, inability to perform pursed-lip breathing, rigidity or limited movement around the diaphragm and accessory muscles, and dyspnea with almost all movement. As these symptoms emerged, the question arose: was a neurological connection driving these high perceptions of breathlessness and disordered breathing patterns?

Look to the Nervous System

With the growing evidence correlating dysautonomia as a condition secondary to Long-COVID, we are learning how to support the body’s nervous system and help find the balance between the Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) and the Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS).

Breathing and the nervous system are deeply connected, and each one can influence the other, for better or worse. Because the breath can be both voluntary and involuntary, it can gauge what is happening within the nervous system. During involuntary breathing, fast and shallow breaths likely correlate to the SNS, ready for action or excitement (fight, flight, or freeze). Whereas involuntary breaths that are slow with prolonged exhales or an occasional pause or sigh likely correlate to the PNS, promoting regrowth and repair (rest and digest). We also have the vagus nerve, which innervates the diaphragm. This action is the key to accessing the PNS response through voluntary diaphragmatic breathing. One can engage in focused abdominal/diaphragmatic breathing and activate the vagus nerve.12 This exercise can assist with lengthening the exhale, slowing down the heart rate, and communicating a relaxation response in the body. This technique is not easy and takes practice and patience to be successful. However, if capable of performing without creating stress, these breathing techniques may be the easiest way to incorporate a sense of calm into the body. An important thing to be aware of with breathing retraining is that it should help to calm the nervous system, not excite it.13

As our program continued to see patients with more complex breathing patterns, the following questions came to mind: What to do if breathing retraining can’t be performed because of the severity of dyspnea? Or what if simply mentioning the word breath triggers rapid, shallow breathing related to an overactive SNS response? Through this smaller subset of patients, we started to explore using the body as a means to trigger a relaxation response. The idea is that if you deliver relaxation through the body, the nervous system will respond, and the breath will follow.

A Solution

We decided to incorporate a specific type of yoga called “The Kaiut Yoga Method.” This style of yoga uses the body as a means to communicate with the nervous system. It is practiced at a slower pace to increase one’s ability to stay in the present moment. Students are guided through yoga poses, allowing them to feel the relationship between their bodies, specifically their joints, and notice their breath while promoting a restful state. Kaiut Yoga can offer a sense of calm in the brain and promote healing benefits through the biomechanics of the body. The practice is taught either in a one-on-one setting or in a group class.14 Through the experience of our team, we are seeing positive results, and the feedback has been supportive. As one patient student with long-COVID commented, “I feel like all is well in the world when I practice”. In terms of breathing, Kaiut Yoga can help improve the overall mechanics of breathing, leading to improved mobility around the rib cage, diaphragm, and accessory muscles. The breath also naturally slows down as a consequence of slowing down the body, thus creating a positive breathing memory in the nervous system.

The ability to deliver a relaxation response in the nervous systems, even if only for a moment, is extremely powerful for healing (remember PNS, regrowth, and repair). Assisting people to find a balance between the SNS and PNS can deliver healing benefits that cannot be measured quantitatively; however, this can be empowering subjectively. This can increase the potential for other treatments to be more effective.

Respiratory Therapists supporting Long-COVID

To be an RT, one must constantly grow and expand our role in the health care system. Now more than ever, the RT role is evolving in new and exciting ways. Pulmonary rehabilitation is an evidence-based discipline based on well-designed clinical trials, with valid, reproducible and interpretable outcomes.15 A concept which is practiced in Pulmonary Rehab is Collaborative Self-Management or the idea of supporting someone as they navigate how to improve one’s condition and well-being. For people living with Long-COVID, this includes helping them to understand this may be a marathon and not a sprint.

For an inpatient RT in the post-acute setting, this might be you listening to someone’s experience through COVID, yes, just listening. If there’s time, perhaps teaching them breathing techniques such as PLB and diaphragmatic breathing. If they are taking inhaled medications, taking the time to educate, remembering they are likely overwhelmed. Outpatient or Pulmonary Rehab therapists may have more time to create deeper connections of support. Education around slow and gradual progression with exercise or movement and breathing retraining breaks while managing symptoms. Pulmonary Rehab RTs can facilitate support for these patients for weeks, months, and possibly longer. Simply being there as a resource, providing encouragement, listening, and legitimizing their concerns, always reassuring them that they are on a healing journey.

Closing

There is no specific diagnostic tool to categorize symptoms related to Long-COVID, nor are there stages of the disease as with other pulmonary manifestations. Each person will present differently, and as is performed in Pulmonary Rehab a detailed assessment and an individualized approach seems to provide the best results. Most of what I have learned comes from the people living with Long-COVID and who I consider to be the heroes in this journey. Their perseverance and desire to heal are inspiring, especially when there is so much we still don’t understand.

References

- “Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Tracker” (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/, accessed August 30, 2021)

- Post-COVID Conditions: Information for Healthcare Providers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Updated July 9, 2021 https://cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/post-covid-conditions.html. Accessed August 28, 2021.

- Lopez-Leon, S., Wegman-Ostrosky, T., Perelman, C. et al. More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 11, 16144 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-95565-8

- Nalbandian, A., Sehgal, K., Gupta, A., Madhavan, M. V., McGroder, C., Stevens, J. S., … & Wan, E. Y. (2021). Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nature medicine, 27(4), 601-615.

- Barizien, N., Le Guen, M., Russel, S. et al. Clinical characterization of dysautonomia in long COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep 11, 14042 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93546-5

- Goodman, B. P., Khoury, J. A., Blair, J. E., & Grill, M. F. (2021). COVID-19 dysautonomia. Frontiers in Neurology, 12, 543.

- What is ME/CFS?: UCenters for Disease Control and Prevention: Last reviewed January 27, 2021. https://cdc.gov/me-cfs/about/index.html Accessed August 28, 2021.

- Fu Q, Levine B. Exercise and non-pharmacological treatment of POTS. Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic and Clinical. Science Direct, 2018: 215: 20

- “Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia” (http://dysautonomiainternational.org/pdf/CHOP_Modified_Dallas_POTS_Exercise_Program.pdf accessed on September 23, 2021)

- Jason LA, Holtzman CS, Sunnquist M, Cotler J. The development of an instrument to assess post exertional malaise in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome. J Health Psychol. 2021;26(2):238-48.

- Thomas, M., Price, O., Hull, J. (2021). Pulmonary function and COVID-19. Current Opinion in Physiology, 21:29–35.

- Bordoni, B., Purgol, S., Bizzarri, A., Modica, M., & Morabito, B. (2018). The Influence of Breathing on the Central Nervous System. Cureus, 10(6), e2724. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.2724

- Gerritsen, R., & Band, G. (2018). Breath of Life: The Respiratory Vagal Stimulation Model of Contemplative Activity. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 12, 397. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00397

- “The Kaiut Yoga Method” (https://kaiutyoga.com/the-kaiut-method/ accessed September 23, 2021)

- “The American Thoracic Society” (https://thoracic.org/members/assemblies/assemblies/pr/ accessed September 23, 2021)

Email newsroom@aarc.org with questions or comments, we’d love to hear from you.