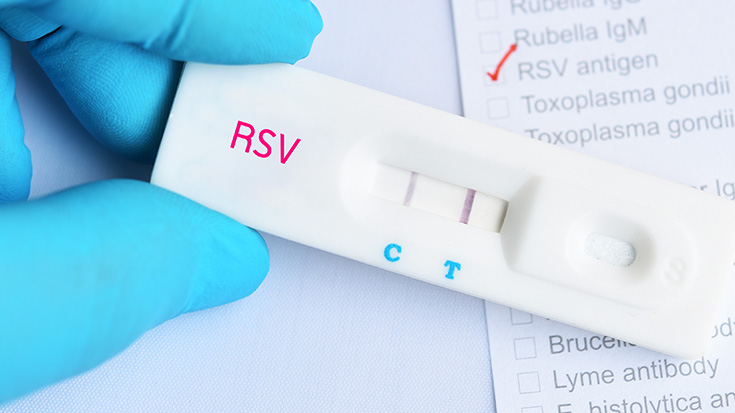

RSV Immunoprophylaxis Timing Needs to be Expanded

More needs to be done to ensure high risk children can receive RSV immunoprophylaxis outside of the typical November-March RSV season, report researchers from Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

They reached that conclusion after studying RSV hospitalizations in kids under the age of two at 40 hospitals across the country between July of 2017 and November of 2022.

Like previous studies, they found RSV seasonality shifted during COVID-19. But despite the fact that the American Academy of Pediatrics encouraged off-season RSV immunoprophylaxis authorization, the shifting season was well underway before high risk children could actually get it, suggesting many were left vulnerable to severe disease.

Their findings on hospitalizations confirmed the worst did happen. High risk children — defined as those with congenital heart disease, prematurity, and chronic lung disease of prematurity — made up a larger portion of hospitalizations between seasons in 2021, and those with public insurance were particularly affected.

Overall, pediatric hospitalizations for RSV in 2021-2022 accounted for 45% of all pediatric RSV hospitalizations over the past five years.

“Our findings underscore the need for a more fluid policy on RSV prophylactic availability so that we can start protecting children at high risk as soon as we see cases rising in the community,” said study author Jennifer Kusma, MD, MS. “Given the recent RSV peaks at unusual times of the year, these kids need access to the prophylactic when the virus actually hits, as opposed to only in November through March.”

The study was published by JAMA Health Forum. Read More

Fixed-Ratio Spirometry Too Often Misses COPD in African-Americans

Fixed-ratio spirometry may fall short when it comes to diagnosing African-Americans with COPD.

That’s the key finding from researchers at National Jewish Health who examined data on current or former smokers with at least a ten pack year smoking history from 21 centers around the country.

Results showed 21% more of the patients who were African-American were classified as non-COPD using the fixed ratio method, even though many of them had symptoms of COPD and some already showed signs of emphysema on their CT scans.

Author Elizabeth Regan, MD, PhD, believes the fixed ratio doesn’t work well for African Americans because many of them have been exposed to various levels of deprivation in their lives that has resulted in smaller lungs with comparatively better airflow.

“When the two aspects of spirometry are combined in a mathematic ratio (airflow/lung volume) the number is higher than would otherwise be expected, leading to the conclusion that they do not have COPD or other lung problems,” she noted. She calls for the development of better diagnostic tools to bridge the gap.

The study was published by the Journal of General Internal Medicine. Read More

Timing of Wildfire Smoke Exposure Matters in Early Childhood

Smoke from the wildfires burning in Canada dominated the news this summer as it traveled into the U.S. and caused significant health problems for susceptible individuals like those with asthma and COPD.

A new study from researchers at UNC Health suggests exposure to wildfire smoke in the womb or in the early days of life may influence respiratory infections in early childhood as well.

The investigators, who collaborated with researchers from the EPA, used data from private insurance claims to link 182,387 live births in Oregon, California, Montana, Nevada, and Idaho to wildfire smoke exposure estimates based on data from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Smoke exposure was measured during each trimester and then at 0-12 weeks and 13-24 weeks. The time to a first prescription for an upper respiratory or lower respiratory infection was noted as well.

The study found first trimester and post-birth exposure to wildfire smoke shortened the time to the first use of upper respiratory medication, while in-utero exposure resulted in an increase in time until the first use of lower-respiratory and anti-inflammatory medications. The time to first use of upper respiratory medication was shorter in female children exposed during the first trimester and the first 12-week postnatal period. It was shorter for male children in the 13-24 postnatal week period.

“The effects measured in the upper respiratory tract were likely caused by infants directly inhaling wildfire smoke via the nasal cavity, while the first trimester effects were indirect via the mother’s exposure,” said study author Ilona Jaspers, PhD. “Infants are obligate nose-breathers and would potentially have significant nasal exposure during wildfire episodes.”

The authors could not explain the unexpected inverse relationship between upper and lower respiratory infections, but said one explanation could be live birth bias. In other words, data in perinatal epidemiological studies are limited to live births and cannot provide information on pregnancy loss. A biological process reaction to smoke in utero might also be coming into play.

The study was published by Environmental Health. Read More

Email newsroom@aarc.org with questions or comments, we’d love to hear from you.