The global pandemic that began spreading throughout the world in the first quarter of last year has significantly impacted just about everyone on the planet. From seniors forced to isolate themselves from their families to children who missed months of in-person instruction, to people who lost their livelihoods due to shutdowns in the economy, the pain has been real.

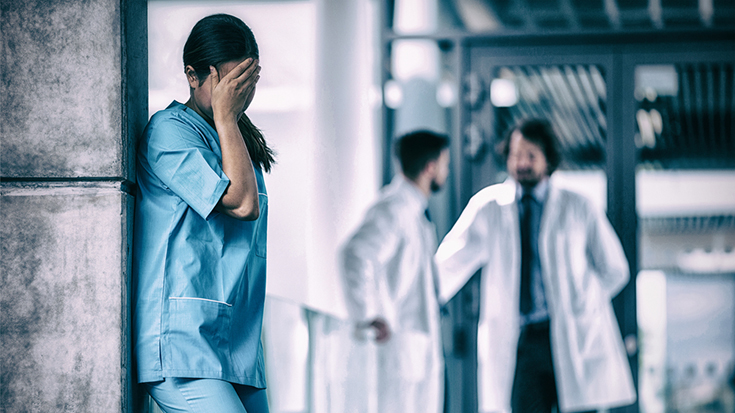

When historians write about this time, though, there will be a special place amidst all this carnage for health care workers. Aside from the patients who dealt with severe illness or, worse, lost their lives, they have borne the brunt of COVID-19.

How have they kept going? We asked AARC members to share their stories.

Wishes he could do more

John Basile, BA, RRT, has been a respiratory therapist for more than 40 years now, and like a lot of people in that position before the pandemic, he probably thought he’d seen it all. But 2020 was a reality check.

“I have never been through something as widespread and long-lasting as this pandemic,” said the RT at Providence/St. Joseph Health & Services-Seaside Hospital in Seaside, OR. It’s been tough for Basile both professionally and personally — he has a 91-year-old mother to think about — but he doesn’t think he’s lost his compassion for patients. “I do not believe I have suffered from compassion fatigue,” he said.

Indeed, he often feels like he isn’t doing enough for his patients.

“I am limiting my time in the patient’s room and sometimes wish I could do more,” he said. “I have found myself feeling guilty for not going to harder-hit areas of the country to help out.”

Basile’s patience has been worn thin, though, by the general lack of public trust in science he saw in the community, and he also believes his expertise as an RT could have been put to better use earlier in the crisis.

“I have wondered if my knowledge of ventilation techniques like APRV or HFNC could have been better utilized in the health system during the beginning of the pandemic,” he said.

Despite these issues, he has been steadfast about keeping his eye on the ball.

“We can do this as part of the team and a profession and feel good about our work,” Basile said.

How he copes: Basile says he keeps himself safe and tries to ensure those around him stay safe as well. And he always maintains hope for the patients afflicted with the virus.

Compassionate weaning is a struggle

As a travel therapist, Kathy Werner, MHA, RRT, was enjoying the opportunity to explore different areas of the U.S. while working at a diverse range of hospitals when the pandemic surfaced last year. COVID-19 put an end to that.

“When COVID hit, I stopped long-distance travel,” she said. “I was afraid of what I would get into and afraid to be far from family.”

For her, the worst part of the pandemic has been the increased need for compassionate weaning in patients with little or no hope for survival.

“Prior to COVID, it was an event that was planned in coordination with the patient’s family and friends and was truly a compassionate process,” said the Florida RT. “Now, the patient is alone, we pull the tube, and we have to move on.”

But there are success stories too, and those buoy her spirits.

“Some patients do get better,” she said. “It can be very rewarding to be able to wean someone off high flow O2 to traditional oxygen, especially when the patient partners in their care.”

How she copes: Werner says she got into health care to help people and make a difference in their lives. That still stands.

“I’m doing that every day working with COVID patients,” she said. “That keeps me going even after 40 years of being an RT.”

36 straight days

In his role as clinical manager of critical care support services in the respiratory therapy department at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, MI, Jonathan Vono, RRT, has seen plenty of compassion fatigue among his staff during the pandemic — and he includes himself in that number.

“When my team was working tons of OT to care for our patients, I made sure to be there, visible and helping in every aspect possible,” he said. “I ended up at one point working 36 straight days until I had to take a day off.”

He believes pushing through the worst of times has made him stronger.

“To keep going, in my mind, builds resilience, not letting the situation take control, but taking control of what you can do during the situation, finding ways to stay grounded and remember who you are and why you do what you do,” Vono said. “Health care is a calling after all and, in the end, our desire to help and heal is a driving force that usually kicks in.”

Vono’s story is especially compelling because he did it all despite getting a personal diagnosis of lupus shortly before the pandemic began and losing five friends and one family member to suicides exacerbated by the lockdowns. When things get tough, he reminds himself that this isn’t the first emerging pathogen he has faced during his time in the profession. He also thinks back to other crises the world has faced, such as 9/11, Hurricane Katrina, and Haiti’s earthquakes, which all elicited a strong desire to help.

He believes breaking down and checking out would be worse for most health care providers than hanging in, and that’s why he and his colleagues are still there, still providing the best possible care to patients.

“As the saying goes, you never know how strong you are until being strong is the only option,” Vono said. “We find our inner strength to get through what needs to be done, care for those that need it, mourn those we cannot save, and pray for everyone.”

How he copes: Staying focused on his MBA program, working out in a makeshift gym he set up at home, meditating, cooking when he can, reading more, talking to his neighbor over the fence, and turning the news off have all helped Vono maintain his equilibrium during the pandemic.

So much tragedy and hardship

As a sleep nurse practitioner at The Ohio State University Lung and Sleep Center in Columbus, Jessica Schweller, MS, APRN-CNP, RRT, RRT-SDS, admits the pandemic has had less of an impact on her life than it has on the lives of clinicians working in the COVID wards and ICUs. But it has still taken a toll.

“I wouldn’t necessarily call it compassion fatigue, but I feel my compassion levels have definitely changed,” she said. “For instance, I see many patients on an annual basis for a PAP follow up and used to start the visit with, ‘How has your year been?’ Well, over this past year, I have completely had to change my course of interview for patients, as the amount of tragedy and hardship I have heard from my patients has been overwhelming.”

Having to forego the open and comfortable relationship she has always had with her patients during office visits has been difficult. The need for masks and social distancing makes these visits less personal than they were in the past. This change occurred when many of her patients had even more sleep issues than they did before COVID arrived on the scene.

“We have many patients who are having trouble sleeping out of fear of the virus or stress due to lost income or family members,” Schweller said. “If patients aren’t having trouble sleeping, then they are on the opposite side of the spectrum and are sleeping all the time because they have nothing else to do, as they are isolated from the outside world, and now depression is settling in.”

Seeing so many patients decline due to the collateral damage caused by the virus is hard to deal with because she doesn’t have answers for many of their problems.

“Some days, you feel bad always blaming it on the pandemic, but what else can you do?” she said.

How she copes: Making time for self-care has made a difference for Schweller. Daily meditation and daily walks during lunch have helped clear her head and ensure she is ready for her next patient.

“I feel that both of these strategies allowed me to really give my patients the best care possible during the most difficult time we had,” she said.

Sleepless nights

The main job of anyone in hospital administration is to ensure the organization has everything it needs to deliver quality care to patients. That job has taken on new proportions in the era of COVID-19, and Kim Bennion, MsHS, RRT, CHC, administrative director of respiratory care services for Intermountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, UT, has felt the pressure at her facility.

“Exposures, RTs testing positive, etc. — it has all kept me up at night,” she said. Leadership in her organization has worked overtime to mobilize the sharing of equipment when needed. They created surge plans for staffing and incentive pay, completed federal pandemic waiver agreements to ensure they met regulations after adjusting for staff and supply shortages, and addressed other fast-moving targets.

“I recall a recent time when we were all working every weekend for seven straight weeks just trying to create contingency plans, work clinically at the TeleCritical Care desk or deliver treats and goodies to weary staff,” Bennion said. ”Quite honestly, it has been exhausting and has impinged on everyone’s personal and professional lives.”

She sees compassion fatigue in staff at her facility regularly.

“This is absolutely a reality,” Bennion said. “Whether it’s watching patients die, exhausted staff, or caring for friends and family members who are COVID positive outside of work, one finds themselves either crying or holding in emotions thinking, ‘Tomorrow, I’ll have time to cry.’”

But if front-line staff can keep going, so can she.

“How in the world can you ask others to keep giving of themselves if you, as their leaders, are unwilling to give right back?” asked Bennion. “We are all in this together no matter the role in health care we play.”

How she copes: Bennion keeps it together by doing something extra for her managers and staff whenever she can, whether providing incentive pay or treats and goodies aimed at raising spirits, if only for a moment. “Unless we care for our staff, they will not be able to care for the patients who so desperately need them,” she said. “We feel the weight of that on our shoulders as leaders.”

Staying the course

Staying the course during this pandemic has not been easy for health care professionals. These RTs found ways to stay dedicated, even when they are just running on fumes. We commend them and respiratory therapy professionals everywhere for their commitment to their patients.

Share your COVID-19 coping strategies in the Communities section of AARConnect.

Email newsroom@aarc.org with questions or comments, we’d love to hear from you.